Cuneiform

|

Map of Mesopotamia Map of Mesopotamia |

Clay tablets from Mesopotamia preserve the world's earliest known forms of writing. For thousands of years, from the 4th to the 1st millennia BCE, writing tablets were used to convey messages, keep records, and transmit literary works in several different languages that are now extinct. Then writing took the form of wedge-shaped symbols that were pressed into blanks of man made clay in the shape of standardized patterns, just as we write a string of letters the make words and then words on a page, via a keyboard. The common cuneiform languages include Elamite, from the large geographical region known as Persia, whose center was based in modern Iran; Sumerian, representing one of the earliest known western civilizations, located in southern Mesopotamia; Hittite, coming from an area stretching from Turkey to Syria and further south; Akkadian, emanating from the area of modern Iraq, near Baghdad; and, Eblaite, the oldest known written Semitic language coming from what is now Syria. Knowing how to interpret the languages left as cuneiform brings forgotten peoples and little-known empires into the light of history. Many thousands of these tablets have been discovered, some from well-excavated contexts. Smaller ones are often called "

tags." Near the city of Mosul, Iraq, at an ancient archaeological site, Assurbanipal's Library at Nineveh, 20,000-30,000 tablets have been found in what may have been palace archives. However, the original sources of many tablets are hard to identify and may never be known, for they have come from unprotected sites that had been looted.

|

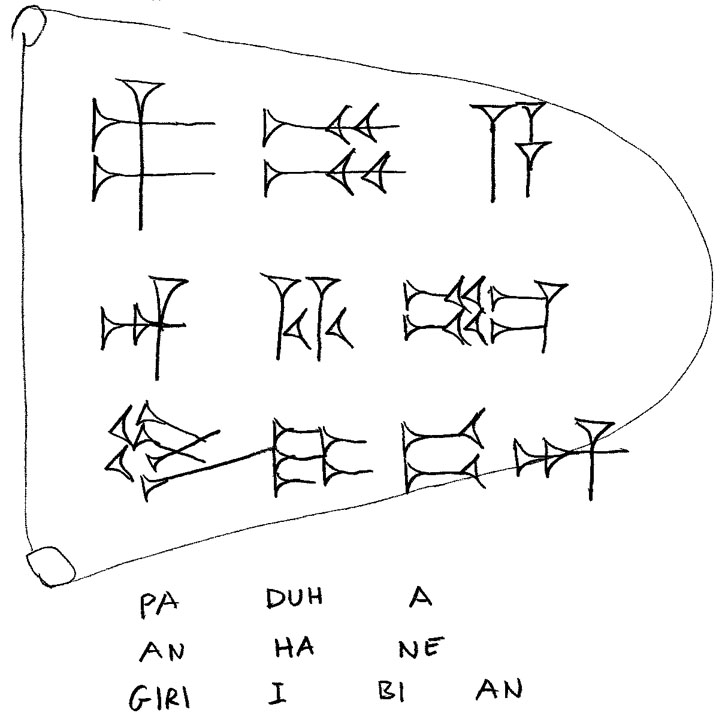

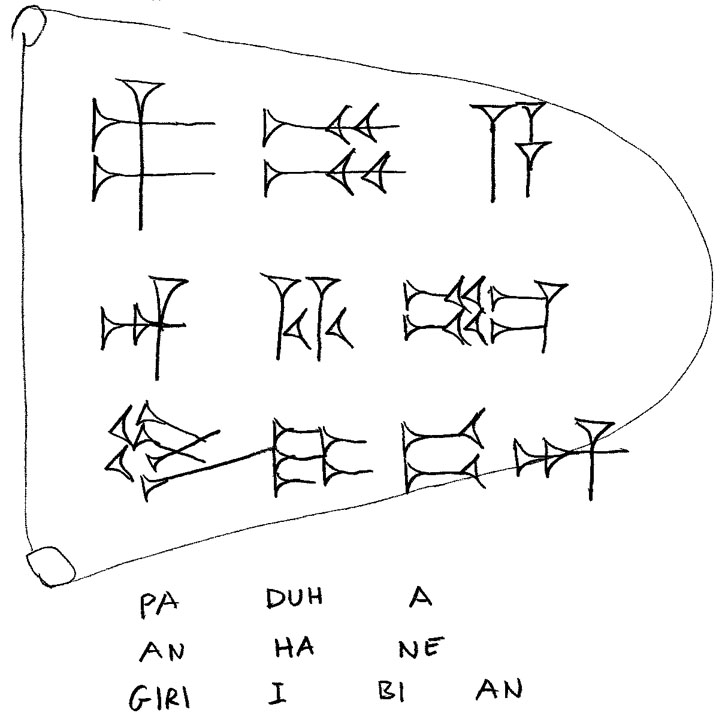

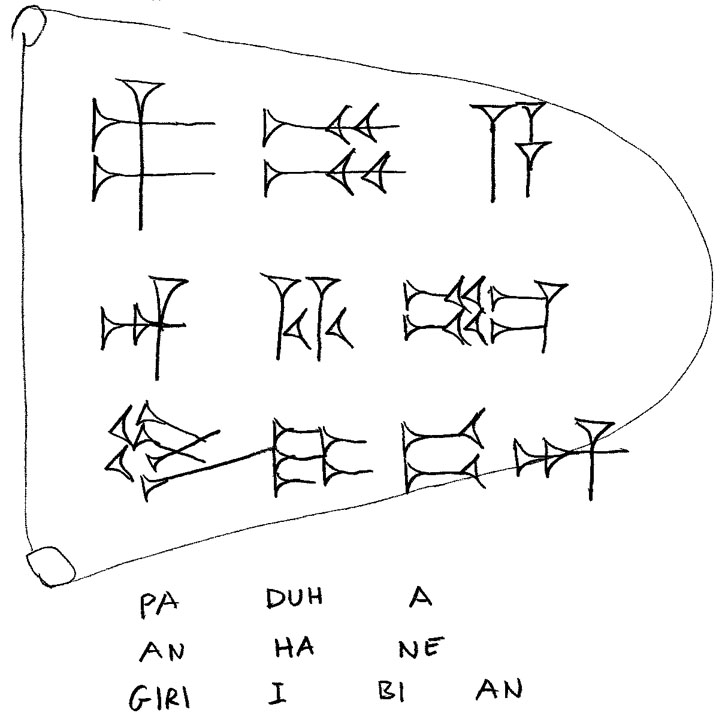

Example of a tag Example of a tag |

The term "cuneiform" refers both to the symbols and the inscription technique used on the tablets. As a method of writing, cuneiform is well suited to its medium. All it takes is a block of flattened clay and a chopstick-like stylus to make the wedges with. The individual symbols evolved into a system of about 750 signs, of which about 300 were in common use by the mid-third millennium B.C. Exactly who wrote the tablets is an interesting question. We know there were specialists, scribes, who acquired this skill by practicing and learning to read and write the signs on "school tablets" under the guidance of teachers. But how widespread "cuneiform literacy" actually was within a population is difficult to say.

Map of Mesopotamia

Map of Mesopotamia

Example of a tag

Example of a tag

Map of Mesopotamia

Map of Mesopotamia

Example of a tag

Example of a tag